Summer 2018

From large organizations, to individual schools, to a single pastor—people are finding a way to bring education to those who need it most. In this issue, learn about Rafiki, an organization dedicated to grassroots education throughout Africa.

WHAT DOES SOCRATES HAVE TO DO WITH CLEAN WATER?

Karen Elliott of Rafiki Ministries gives us an answer:

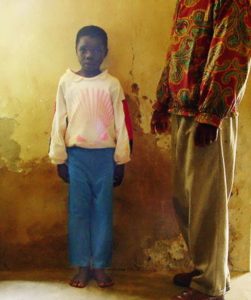

“In 2000 the Kaduna riots broke out in Nigeria. Conflict turned to violence at the introduction of sharia law when the majority non-Muslim population resisted. At the time, a young boy named Fidelis lived with his mother, father, and sister in a small village. One day a group of tribal Muslims attacked their village. Fidelis watched in horror as the assailants cut down both his mother and father. In desperation he fled to his house, jumped into a large water vessel—which happened to be empty—and hid inside for several hours until the assailants left. He finally emerged from his hiding place, only to find the lifeless bodies of his parents.

Through the sovereignty of God, Fidelis was brought to Rafiki.

Rafiki Africa Ministries operates villages throughout Africa. Each village includes an orphanage, preK–12 school, and teacher college centered around classical Christian education. For 33 years, Rafiki has worked to help children know the love of Jesus and raise their standard of living. Rafiki’s instinct to employ education to mitigate the poverty, disease, and corruption that has plagued the African continent for centuries is not particularly unique. 100 years ago, colonial powers likewise deemed accessible education the best way to boost Africa’s standard of living. They suggested purely vocational training would best equip students to work, emphasising the practical studies of health and agriculture. The results have been disappointing. The narrow, specialized exposure to subjects has produced narrowly interested albeit capable students, unable to synthesize ideas and lacking in innovative imagination: the precise skills needed to resurrect Africa from poverty.

Rafiki Africa Ministries operates villages throughout Africa. Each village includes an orphanage, preK–12 school, and teacher college centered around classical Christian education. For 33 years, Rafiki has worked to help children know the love of Jesus and raise their standard of living. Rafiki’s instinct to employ education to mitigate the poverty, disease, and corruption that has plagued the African continent for centuries is not particularly unique. 100 years ago, colonial powers likewise deemed accessible education the best way to boost Africa’s standard of living. They suggested purely vocational training would best equip students to work, emphasising the practical studies of health and agriculture. The results have been disappointing. The narrow, specialized exposure to subjects has produced narrowly interested albeit capable students, unable to synthesize ideas and lacking in innovative imagination: the precise skills needed to resurrect Africa from poverty.

Students cannot consider new political regimes if they have only ever learned how to grow a tree. They cannot dream of going to the moon if they have never studied the solar system. They cannot recognize a tyrant if they have not studied the virtues of a good leader. The proposed system of vocational training severely limited students’ capacity to understand broad ideas and inspire social change.

Africa’s current model engages students at a very superficial level, grading students only according to short-answer tests and little else. Students are not encouraged to ponder questions or consider long-term implications of the answers; instead they are taught to merely pass unit tests. According to Rafiki Executive Director Karen Elliott, “cram, pass, forget” largely sums up the current African model of education. It sounds familiar.

Not only is the structure itself broken, but its application has been noncommittal at best. Teachers attend only about 60% of their own classes, and those employed register at a fourth-grade math level and a seventh-grade reading level. Teachers use no curriculum, with 60–70 students per class. This is true even among church schools, which are often Christian in name alone, as they employ only government-certified teachers and teach no biblical material at all.

SOCRATES?

The Rafiki Foundation takes a common solution one step further: instead of simply training Africans for specific jobs, Rafiki has implemented classical Christian schools to broadly expose students to enduring ideas, to teach them to love what is good and praiseworthy, and to train them to articulate those ideas with clarity and excellence. Instead of merely engaging the student’s mind to pass a test, Rafiki engages his whole person, focusing on the merits of the student himself instead of the difficulty of the test. Instead of preparing the student to get by in the existing social system, Rafiki equips him to change the structure of the system itself.

The Rafiki Foundation takes a common solution one step further: instead of simply training Africans for specific jobs, Rafiki has implemented classical Christian schools to broadly expose students to enduring ideas, to teach them to love what is good and praiseworthy, and to train them to articulate those ideas with clarity and excellence. Instead of merely engaging the student’s mind to pass a test, Rafiki engages his whole person, focusing on the merits of the student himself instead of the difficulty of the test. Instead of preparing the student to get by in the existing social system, Rafiki equips him to change the structure of the system itself.

The Rafiki Foundation currently maintains ten Rafiki Villages in ten African countries. This is the largest-scale implementation of the liberal arts ever attempted on the continent. At this point, missionaries still run the villages, but the villages are intended to gradually become indigenous ministries.

Over the years Fidelis has grown into a kind, hard-working young man. Due to his exceptional ingenuity and mathematical mind, Fidelis began to stand out academically among his peers. He now takes courses through Bingham University, with the goal of becoming a computer programmer.

When he last visited his home village, they all remembered him as “the boy in the pot” and were amazed at how far he had come since that time.

Fidelis was once asked about his favorite hymn. He responded, “O the Deep, Deep Love of Jesus” because “after singing this, I always asked the Lord God to search me, O God, and know my heart. I always asked God to help me love my brothers and sisters and to give me the heart to love my enemies even though they killed my dad and mom. Whenever I sing this song, I always feel closer to God and feel His presence with me.”

We believe CCE is the best education for the whole human being, the best way to train a child in Christ, and the best way to teach a child how to think. We long to see each child reach his or her highest potential in order to transform Africa spiritually, educationally, and economically. The key to doing this is to enlist additional child sponsors. We are praying that all of our children, over 25% of whom are not fully sponsored, will reach full sponsorship this year.May God bless you as you give—that a child like Fidelis in Africa might know God and have a bright future of life and service to Him.

We believe CCE is the best education for the whole human being, the best way to train a child in Christ, and the best way to teach a child how to think. We long to see each child reach his or her highest potential in order to transform Africa spiritually, educationally, and economically. The key to doing this is to enlist additional child sponsors. We are praying that all of our children, over 25% of whom are not fully sponsored, will reach full sponsorship this year.May God bless you as you give—that a child like Fidelis in Africa might know God and have a bright future of life and service to Him.

We offer multiple sponsorships per child. With $25 a month, sponsors receive regular updates on their child’s successes and prayer concerns. Monthly sponsorships or one-time donations are appreciated.

Phone: 352-483-9131

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: RafikiFoundation.org

![]()

Thank you, Karen, for this timely article. The first part accurately describes education in my country, Cameroon. I have a vested interest in using Christian education as a means of transforming the next generation of Cameroonians with the gospel Christ.