By David Goodwin

How Hollywood lost its way

Have you noticed how the stories in our most popular story form—the movies—have paled in recent years? In 2019, the top 10 movies were: Avengers Endgame (sequel), The Lion King (remake), Frozen II (sequel), Toy Story 4 (sequel cubed), Captain Marvel (concept sequel), Rise of Skywalker (umpteenth sequel), Spider Man (sequel), Aladdin (remake), Joker (spinoff), It (sequel). Not until position 18 do you get an original story—ironically called Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Why is Hollywood struggling to find new stories? Because, for the first time since Plato, the West has lost sight of its grand narrative.

The Frankfurt School was a group of 20th-century, mostly German philosophers who were bent on spoiling everything true, good, and beautiful. They gave us critical theory, identity politics, the sexual revolution, and many of the bad ideas our culture—and many of us—are now embracing. One postmodern philosopher nearing the orbit of the Frankfurt gang was Jean Francois Lyotard. He described postmodernism as “incredulity toward meta-narratives. ”In other words, we no longer believe in a transcendent true story that animates and illuminates all of our lesser stories. He criticized the Western mind because “the narratives we tell to justify a single set of laws and stakes are inherently unjust.”

In fact, we cannot be incredulous toward all meta-narratives. We have to believe something about our world. But we can reject transcendent meta-narratives, in favor of ones where the ultimate hero is us. The problem: this puts our stories in a boring brown box.

Two Competing Grand Narratives

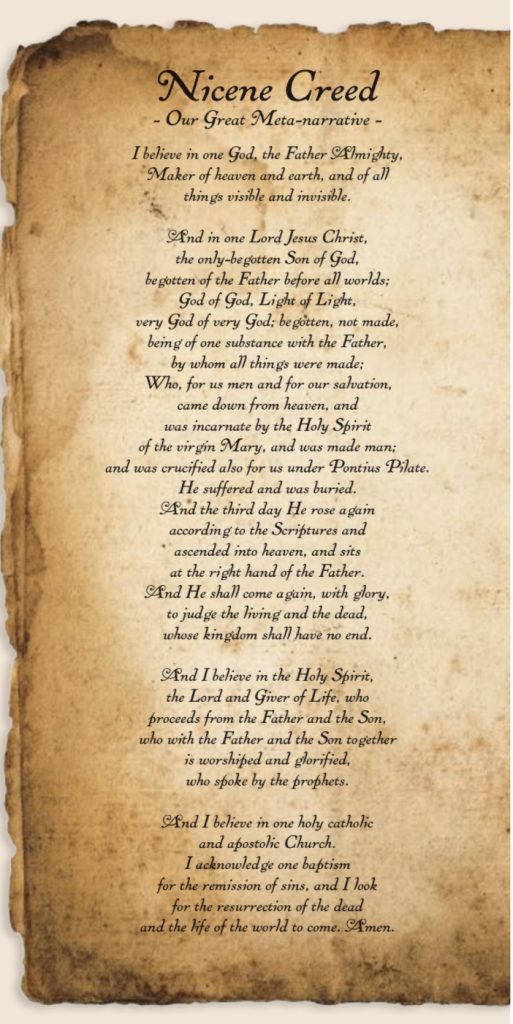

For some time, our meta-narrative made our lives and our stories rich, as it was carried through our creeds, and in Scripture. One of the best summaries of the Christian narrative is the Nicene Creed. This narrative brought us to love true, good, and beautiful things—not according to our personal standards, but by the standard of an infinite God. To borrow an old phrase, this meta-narrative “hitched our wagon to a star.” Every princess could be an avatar for the church, every prince could be a Christ figure, every witch a stand-in for a demon, and every dragon the Father of Lies. Under the span of this meta-narrative, most of the greatest stories have been written—The Divine Comedy, Frankenstein, Moby Dick, Pinocchio, Huckleberry Finn, Robin Hood, A Tale of Two Cities, The Last of the Mohicans, The Fellowship of the Ring, and on, and on.

The grand (but not transcendent) narrative that replaced the Christian one is now held, at least in part, by nearly all Americans. It is that of progress. In this story, humans were once lesser animals that grew increasingly sophisticated, to the point of believing in gods. Through reason and science we progressed past our need for gods, or God, and now we are on our way to controlling our own destiny. Our heroes are those who advance science to further escape even those physical limitations still imposed on us by nature.

progress. In this story, humans were once lesser animals that grew increasingly sophisticated, to the point of believing in gods. Through reason and science we progressed past our need for gods, or God, and now we are on our way to controlling our own destiny. Our heroes are those who advance science to further escape even those physical limitations still imposed on us by nature.

This grand narrative explains everything from the extremes we take to stop a virus, to the sudden surge in gender “transitions,” to increasing contempt for free societies. As the Millennials and Gen Z-ers fully embrace the progressive narrative, our stories fade. Life fades. And, meaning fades. We are left only sensationalism and bland pleasures. And soaring rates of depression.

This brings us to our current Classical Difference issue on literature.

Near the height of the widespread immersion in the Christian narrative, the novel was born (see page 15) and, for example, Hans Christian Andersen wrote The Snow Queen. In it, a troll makes a magic mirror that reflects only the bad or ugly side of the person or thing. The mirror is accidentally shattered into dust and spread across the earth, where it gets into people’s hearts and eyes and makes them only able to see the bad and ugly in others (original sin). One boy is infected by the mirror and, in his descent into ugliness, is cruel to his friend Gerda (the Christ figure). He meets the Snow Queen (the Satan figure) who kidnaps him. Gerda goes on a quest to save him, despite his cruelty to her (self-sacrifice). The girl’s childlike innocence gives her the power to defeat the Snow Queen (with the Lord’s Prayer), and she restores her friend with a kiss (the power of love to save). It’s easy to see the alignment with the Christian narrative of evil, sin, love, salvation, and purpose.

But it’s not really about cognitively seeing it. Over thinking the story saps the life out of it. Stories that run alongside a true meta-narrative, yet remain their own, are like harmonies in a song. You hear Art Garfunkel’s melody, but Paul Simon’s harmony makes the sound you love. Stories need to harmonize with a greater narrative or they fall flat. If your grand narrative does not contain a disdain for ugliness, or a love of mercy and grace, or the reality of sin, or the honor in self-sacrifice, then stories like Andersen’s won’t change you or even seem interesting. It’s like two dissonant chords, with notes grinding against each other.

Trinity Christian School, Kailua, HI

Disney has tried to revive its princess franchise in a world that no longer loves many of the things that make princess stories work—like hierarchy or a divine order in all things. Our new grand narrative no longer draws us to love a King. This presents a challenge when your franchise is based on royalty! So, with a series of ho-hum attempts at a modern princess based in other meta-narratives (Pocahontas, Mulan, Moana), they turned to Hans Christian Andersen. In Frozen, Disney distorts the original “Snow Queen” story, but leaves it intact enough to harmonize with the lingering tones of a fading Christian meta-narrative—self-sacrifice, the importance of self-control, and the power of love to save.

The good news is that classical Christian education cultivates a deep Christian meta-narrative in its study of God (theology). The result is that the great stories of the past, and a few of the present, have a magnetic pull on our children’s souls toward the true, the good, and the beautiful. Read these stories to your kids. Find the Christian meta-narrative on occasion. See if your children can pick out the harmony. But most of all, just let your children enjoy a great story. ✤

DAVID GOODWIN

President, ACCS