Read Part 1: Legends of America: Ashley’s 100

Century Watch

This Year in History: A.D. 1823

Today people usually call them mountain men—the trappers of the Rocky Mountain West. Popular literature and movies often portray them as “crusty old coots” providing comic relief in cowboy stories. But in their prime, fifty years before the West of the cowboys, the mountain men lived a mythic period of American history. This was the West of Hugh Glass. They usually called themselves mountaineers rather than mountain men. They were mostly young, in their twenties and thirties. Daring, curious, fiercely independent, or rebellious, each of them chose to leave the familiarity of the settlements to take part in one of the first commercial enterprises of the American West—the fur trade.

Hugh Glass survived what appeared to be certain death at least six times in his life. His greatest story of survival, and the one that made him a legend, began in August of 1823. When Glass walked into Fort Kiowa in October—seemingly returned from the dead—his story became a tale of mythic proportions.

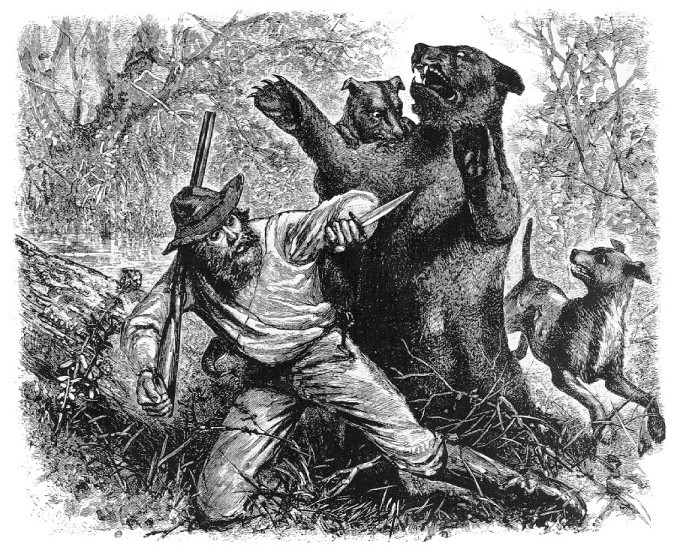

Hugh Glass’ survival against the odds—mauled by a grizzly bear, left for dead without weapons or equipment to survive or die alone—was a story so amazing that it became legend even among the mountaineers themselves. Recounted around camp fires during Glass’ own lifetime, the story made it into print a mere two years after the incident, and the drama of it still echoes today.

—Scott Walker, HughGlass.org/mountain-man/

1822: Ashley’s 100

Hugh Glass had already had his share of adventure before the fateful day in 1822 when he picked up a newspaper in Missouri. Captured in the Gulf of Mexico by the pirate Jean LaFitte and facing execution, he jumped overboard and escaped through Texas only to be captured in Kansas by the Pawnee, who made a ritual sacrifice of his companion. Glass bartered for his life with Vermillion (prized for war paint) and lived with the Pawnee, eventually making his way back to St. Louis.

There he saw an ad for an entrepreneurial trading venture seeking 100 young men. They became known as Ashley’s 100, and many would become American legends, including Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith, and Hugh Glass.

1823: Left for dead

In August of 1823, Major Henry, co-leader of Ashley’s 100, was leading his group to Fort Henry at the mouth of the Yellowstone River in Montana. Near the Grand River in South Dakota, Glass, working as a scout ahead of the group, stumbled upon two bear cubs. Within seconds he was attacked by the mother grizzly bear. The men heard his screams and killed the grizzly, but the bear broke Glass’s leg, ripped open his scalp, punctured his neck, ripped his back to the bone exposing the ribs, and left gashes and bites all over his body.

Glass unexpectedly survived the night. Being in hostile Blackfoot territory, it was imperative that they move quickly, so they pulled Glass for two days on a handmade litter. On the third day, Major Henry offered $80 each for two volunteers to stay behind and give Glass a Christian burial. John Fitzgerald and Jim Bridger volunteered. Glass remained alive for five days, but the only sign of life was his shallow breathing and occasional eye movement. Fitzgerald became increasingly paranoid of attack, and convinced the 18-year-old Bridger that Glass could not survive and that they had fulfilled their part of the bargain. Before leaving, they put him in a shallow grave next to a stream and took his gun, knife, tomahawk, and fire-making kit—everything a healthy man would need to survive in the wilderness.

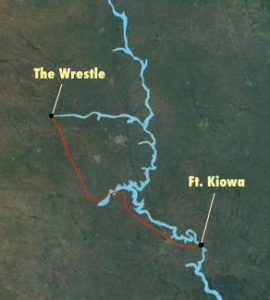

It did not take long for Glass to realize he had been abandoned. He pulled himself out of the shallow grave and with only one working arm and leg, and his back still exposed to the bone, he began to drag himself back to Fort Kiowa, 250 miles away. He ate bugs, plants, insects, snakes, and whatever else he found as he went. Eventually, he was able to crawl. When he came across a pack of wolves eating a buffalo calf on the prairie, he waited till they finished and then took the rest of the carcass. He ate the raw meat, staying until most of it was gone, and gaining enough strength to move from crawling to walking. Eventually, he reached the Missouri River, and floated the rest of the way on a skin boat.

250 miles away. He ate bugs, plants, insects, snakes, and whatever else he found as he went. Eventually, he was able to crawl. When he came across a pack of wolves eating a buffalo calf on the prairie, he waited till they finished and then took the rest of the carcass. He ate the raw meat, staying until most of it was gone, and gaining enough strength to move from crawling to walking. Eventually, he reached the Missouri River, and floated the rest of the way on a skin boat.

He walked into Fort Kiowa in mid-October, two months after the grizzly attacked him.

He immediately began to track down Fitzgerald and Bridger. Within a few days, he joined a group heading upriver toward Fort Henry, Montana. As they neared a Mandan village, Glass went ahead on his own to make better time. He was spotted and chased by a group of Arikara warriors, but in an extraordinary turn of events, two Manden Indians were watching. They swooped in on horseback, grabbed Glass, and took him safely to nearby Fort Tilton. There Glass found out that all of his group had been killed by the Arikara while he was away.

Glass continued alone to Fort Henry, where he met half of his goal—Bridger. He soon realized Bridger was an inexperienced youth influenced by the older Fitzgerald, and legend says that he forgave Bridger, letting him off with a warning. Fitzgerald, Glass was told, had left the Ashley men and was at Fort Atkinson in Nebraska.

In February 1824, Glass and four men left Fort Henry for Fort Atkinson, to deliver a message from Major Ashley to his partner, Andrew Henry. While on the Platte river, they were flagged down by what appeared to be a friendly group of Pawnees. Upon coming ashore, Glass heard the Arikara language. Realizing they were in enemy territory, they made a run for it. Two men were shot and killed, and Glass and the others were separated. Glass again was alone in the wilderness, several hundred miles from civilization, in hostile Indian territory, with no rifle. Glass said later to a fellow mountaineer:

Although I had lost my rifle and all my plunder, I felt quite rich

when I found my knife, flint and steel in my shot pouch. These

little fixens make a man feel right peart when he is three or four

hundred miles from anybody or any place.

This no doubt was a perspective he gained after being left with nothing by Fitzgerald and Bridger. The other two men found each other and made it safely to Fort Atkinson in May of 1824, believing Glass to be dead. Glass made it to the Fort in June, one month later.

As the story goes, upon reaching Fort Atkinson, Glass confronted Fitzgerald. But Fitzgerald had joined the military, and the commanding officer told Glass that if he killed Fitzgerald, the army would then have to execute him. Fitzgerald was ordered to return Glass’ rifle and belongings. Glass told Fitzgerald that if he ever left the army, he would kill him, and as far as records show, Fitzgerald never left the army.

American Folk Hero

In the spring of 1833, Glass was trapping with two other men near the junction of the frozen Bighorn and Yellowstone Rivers in Montana, when all three men were shot by a large party of Arikara. Their scalped and plundered bodies were found soon after by Ashley man James P. Beckwourth. Glass and the two men with him were mourned by those who knew them, including the local Crow Indians who thought highly of them. Hugh Glass’ burial place is unknown. ✤