Further Study | More Artwork from the Spirduso Studio | More of the Story

AN INTERVIEW WITH Ken Spirduso

“When I arrived at the Disney studio and began working in Layout, Aladdin had just left our department, so I began work on a Roger Rabbit short called ‘A Trail Mix-up.’ My first feature with Disney was The Lion King, then I worked on Pocahontas, Hunchback of Notre Dame, Mulan, John Henry, Tarzan, Lilo and Stitch, Brother Bear and My Peoples.

Working at the Florida Disney studio was like attending an advanced graduate program—it was the best training I could have received. Looking back at my first introduction to artists such as Howard Pyle, I had longed to follow in that artistic legacy of classical art and storytelling. While my education was a bit piecemeal, I did eventually receive training in both classical art and storytelling through the University of Kansas, Atelier Lack, Sullivan-Bluth, and Disney.

The Layout Department was tasked with designing the backgrounds or environments for the films and designing camera moves, compositions, and staging for each scene. It was part of the fine art wing of the studio, which was filled with some of the most talented artists I’ve ever met, highly trained artists who were constantly working on their craft. It was inspirational to see their sketchbooks.

What caught me by surprise was how the Disney studio was influenced by artistic movements of the past. The legacy of Renaissance drawing was carried on through [the modern art of] animation, but the artistic heritage of the Golden Age of Illustration also found a home in the Disney studios. And this makes sense, since Walt Disney pulled many artists from the illustration ranks early in the studio’s history.”

STORYTELLING IN THE DISNEY WORLD

Q: You mention that the classical approach is inherent in much of Disney’s artistry. How does that approach actually function in practice?

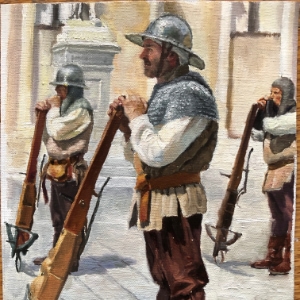

A: Every film project has its own language, a set of rules that govern the visual elements to assist in storytelling. Artists have employed this approach throughout history: how you say something visually can either support or undermine your message. So we made sure that the lines, shapes, tones, sense of space, color, rhythm, and movement worked in harmony with the story. For example, if the story took place in a dangerous world, the environment would appear threatening with sharp shapes, darker tones, and desaturated color.

The use of these visual components is governed by the Principle of Contrast and Affinity. According to Bruce Block, the director and visual consultant who often worked with us at Disney, contrast creates greater visual drama while affinity creates less visual drama. Components such as line, shape, tone, and space can be used to create contrast during climactic points in the story.

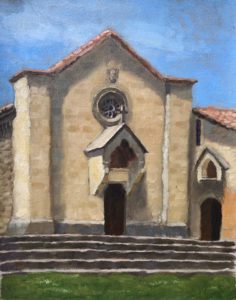

We also tried to be as accurate as possible. What is the landscape of Africa? How was Jamestown designed? What does Notre Dame look like both inside and outside? The studio would send teams of artists around the world to bring back this information, and we would apply that information to our layout drawings and background paintings. We didn’t just want to draw a tree, but a tree that was accurate in its appearance and that helped tell the story.

Starting with what was real, we then filtered it through the style prescribed by the directors and art directors. For example, Lilo & Stitch was about a little girl. Her design was made up of round, innocent shapes so the backgrounds echoed her design. The rocks were round and soft, the trees had round edges, even the edges of furniture looked sanded down. The directors wanted to convey that the ocean had a major influence on the characters’ culture. So, when spacecraft appeared in the movie, undersea life was used as the basis for their design.

Q: Did you as a Christian have a different approach to storytelling or a different opinion about the way stories were being told?

A: No, I don’t think so. The approach to good storytelling seems to be a universal approach, shared by most cultures. The hero story that is so common in our stories, I believe, is a retelling of the story of Christ and a longing for a Savior.

WORK: THE GRAMMAR OF ART

Q: What is the most basic element of a classical approach to art that you believe is missing for many students today?

A: It’s the ability to draw with accuracy. Artists of the past were given observational tools so they could capture the world around them with fidelity and feeling. They were taught at an early age to move from communicating with visual symbols to recording what was actually there in front of them.

The key is to focus on shapes—the shapes of light and shadow, and the shapes that surround an object. By turning our attention away from the object and instead observing the shapes that make up that object, students can effectively capture what they actually observe.

Many artists of the past were masters by their late teens. Michelangelo, Van Dyck, Velazquez, and Rembrandt are examples. I believe it’s because they learned to draw early in their lives. In our day, more emphasis is placed on self-expression. While that is an important aspect of art, students need to first learn how to communicate using the basic grammar of art, just like they need to learn English grammar to write effectively.

The grammar of art is made up of visual components such as line, shape, space, tone, color, rhythm and movement. These are the building blocks of art and comprise every image we create.

Q: Is there a key to achieving the mindset of the great artists?

A: Sherlock Holmes holds one of the keys for artists in his iconic line to Watson, “You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear.” Watson is often frustrated by his apparent inability to see the evidence that only Holmes can; however, Sherlock points out that he doesn’t see different information. He observes the same information in a different way. That’s exactly what artists are trained to do.

If we were able to go back and watch Rembrandt paint, we would see the same visual information that he did. But classically trained artists of the past were handed down effective ways to observe the world so they could translate it into paint and capture it on canvas.

While most people don’t know how to observe a subject and are forced to rely on symbols to communicate visually—for example, a triangle on top of a post is understood as a Christmas tree—artists are trained to observe the actual shapes in front of them, which bypasses those symbols we all learned as children.

SEE: THE LOGIC OF ART

Q: How does classical education develop the ability to see like an artist?

A: Learning to draw classically can be compared to learning Latin. Latin is the basis for so many languages that it makes learning one of those modern languages easier. Similarly, drawing is the foundational language of representational art. The more proficient students are at drawing, the better they can express themselves. It is more than being able to hold a pencil—it’s training students how to look at subjects in order to capture them. Study the past and its artists—then you will learn to see as an artist.

One of the areas of study within classical art is the Renaissance approach. These artists were heavily influenced by Plato, so they began looking for the beautiful, ideal shapes behind and underneath the human body, and they translated them into geometric shapes. Animation is part of that legacy, drawing straight from the Renaissance using circles and cylinders and cubes.

Artists of the past had the discipline to draw and paint from direct observation, which gave them the tools to capture the beauty in front of them. Working from direct observation also provided them with a mental library of unique shapes, tones, and colors that they could use for imaginative works. These skills open up a new world for young artists, and equip them to make a living as an artist.

TELL: THE RHETORIC OF ART

Q: You mention being able to communicate to others in a way they can understand. What do you mean by that, and how do artists learn it?

A: Just as in the Sherlock Holmes adventures, the evidence is there for all to see. It’s the job of the artist, however, to point to that evidence of truth and beauty so others can appreciate and understand it. Artists can also be storytellers, capturing the action of a written story to help the imagination of the reader, or capturing a person’s life story in a portrait painting.

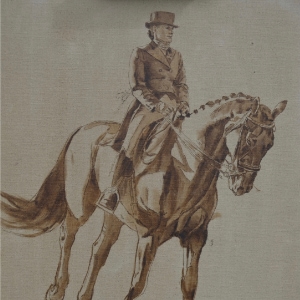

Communicating effectively through the visual arts is helped by an understanding of the world’s design. For example, an equestrian artist needs to know the bones and muscles that make up the horse. Great artists also communicate their own excitement for their subjects. Looking at the equestrian paintings of George Stubbs or Sir Alfred Munnings, the viewer senses the love and wonder these artists experienced in the presence of these magnificent animals. The great masters of the past used their eyes, minds, and hearts—not just their hands—to create beautiful work and to communicate effectively with others.

Spending time in the Scriptures changes how I look at the world, how I look at others, how I look at landscapes. Memorizing great poetry and reading the great books influences my approach to art and my understanding of life. I like what C.S. Lewis said about the blind spots history finds in every age of man: “The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books. Not, of course, that there is any magic about the past. People were no cleverer then than they are now; they made as many mistakes as we. But not the same mistakes.” If we focus only on the here and now, we cut ourselves off from this wisdom and that affects everything, including the artistic process.

CREATIVE LICENSE

Q: How does your love of art inform your faith and vice versa?

A: In wrestling with that question over the years, I’ve found the words of men such as German scientist and mathematician, Johannes Kepler, to be very helpful. He said that his work was “…merely thinking God’s thoughts after Him.” That could be said of an artist as well. The Dutch artist, Rien Poortvliet, once said that he attempted “… to show what the good Lord has made,” which articulates what I have tried to do. I have struggled throughout my life with perfectionism, whether it was in sports, music, or art. I understand now that my perfectionism was my futile attempt at justifying my existence. It was actually in response to God’s law pressing down on me, showing me how far short I was falling according to His perfect standard. Now that I know Christ fulfilled His law for me, won forgiveness for me on the cross, and covered me in His righteousness, I can paint freely to His glory without fear of failure. Those perfectionist struggles can still resurface, but I now have an effective way of dealing with them.

Art can easily become an idol—it has in my life. During my 5 1⁄2 weeks in Florence, Italy, earlier this year, I saw in person the awe-inspiring artwork of the Renaissance. The architecture, painting, and sculpture are breathtaking. However, a fellow faculty member shared with me a surprising sonnet written by Renaissance artist Michelangelo late in life that captures the futility of making art an idol:

The course of my life has brought me now

Through a stormy sea, in a frail ship,

To the common port where, landing

We account for every deed, wretched or holy.

So that finally I see

How wrong the fond illusion was

That made art my idol and my King,

Leading me to want what harmed me.

My amorous fancies, once foolish and happy

What sense have they now that I approach two deaths

The first of which I know is sure, the second threatening.

Let neither painting nor carving any longer calm

My soul turned to that divine Love

Who to embrace us opened His arms upon the cross.

Looking at his later artwork, we still can see Michelangelo’s uncanny ability to capture light, form, anatomy, and movement, but to me there’s something deeper. It’s artwork that wasn’t meant to appease an idol but to humbly thank a Savior. I’m inspired by the Old Testament artist, Bezalel, who was called by God to design and adorn the Tabernacle. He used his gifts in the vocation of an artist to glorify God and serve his neighbors.

NOTES FOR ASPIRING ARTISTS

Q: What would you say is the best way for aspiring artists to train for an actual job?

A: First, I would want students to know the reality of life as an artist, how difficult it is to be successful, and how much work it takes to become proficient. It’s one of the most difficult career paths someone can take, and very few people actually make a living from their artwork. It’s an important vocation, however, and with hard work, diligence, and a lot of prayer, a person can succeed. While a student at KU, I was warned by John Collier how difficult a career in art would be; however, that reality didn’t sink in until I had graduated and began to struggle to make a living. My “Plan B” was continuing to play music professionally, so there wasn’t much of a fallback. I could either starve while drawing or drumming!

For students serious about becoming artists, I recommend the following:

1) Draw as much from life as possible.

2) Keep a sketchbook handy at all times and draw constantly. If you have a particular interest in animals, sports, vehicles, people, or buildings, stay motivated by sketching those subjects. Many students want to immediately jump into digital work; however, a computer program can be learned in a relatively short amount of time. Learning to draw takes a lifetime.

3) Draw from a plaster cast, which has been used throughout the centuries to teach artists to see and understand light, form, and edges. When placed under a bright light source, the plaster cast allows students to observe strong light and shadow shapes, without the complexity of color.

4) Train with experienced artists as early as possible and continue to train into your college years.

Q: Do you have any recommended books?

A: For basic drawing, especially using the Renaissance method, How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, by Stan Lee and John Buscema is a very helpful book. Former Disney artist, Ken Hultgren, wrote and illustrated a book on drawing animals, The Art of Animal Drawing.

I would also recommend that students copy master drawings. There are many books and internet resources that have very good reproductions. Try to copy those drawings as closely as possible.

KEN SPIRDUSO as interviewed by Stormy Goodwin. Ken Spirduso is an educator, painter, and concept illustrator. He and his wife Caroline have two children. They love animals, especially dogs and horses.

KEN SPIRDUSO as interviewed by Stormy Goodwin. Ken Spirduso is an educator, painter, and concept illustrator. He and his wife Caroline have two children. They love animals, especially dogs and horses.

Further Study

I now understand that worldview influences artwork. One of my favorite books is “State of the Arts” by Gene Edward Veith in which he explains the philosophical movements that guided the visual arts. As a student, I merely studied schools of art as a means to understanding technique. I never asked the important and interesting questions, “Why did Monet paint differently than Rembrandt?” “Why does the Renaissance wing of a museum look different than the Baroque wing?” Understanding that the look of art is driven not only by technical innovations but by the worldviews behind it is fundamental to an art education. — Ken Spirduso

Reading List:

•The Visual Story, by Bruce Block

•Harley Brown’s Eternal Truths for Every Artist (Some nudity)

•State of the Arts, by Gene Edward Veith

•Mind of the Maker, by Dorothy Sayers

•Modern Art and the Death of a Culture, by H.R. Rookmaaker

•The God Who is There, by Francis Schaeffer

•The Defense Never Rests, by Craig Parton

•The Liberated Imagination, by Leland Ryken

•Angels in the Architecture, by Doulgas Jones and Douglas Wilson

| Resource | Media | Components to Study |

|---|---|---|

| The Adventures of Tin Tin | Film | Value, Shape, Line, Color |

| The Lord of the Rings Trilogy | Film | Line, Shape, Space, Value, Color, Movement, Rhythm |

| The Incredibles | Film | Line, Shape, Value, Color, Movement, Rhythm |

| Treasure Island, Written by Robert Louis Stevenson, Illustrated by N.C. Wyeth | Book | Shape, Value, Color, Rhythm |

| Shakespeare Illustrations in Pen and Ink, Edwin Austin Abbey | Drawings | Line, Value |

| The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, Written and Illustrated by Howard Pyle | Book | Line, Value, Rhythm |

| Richard Parkes Bonnington | Paintings, Drawings | Space, Value, Color |

| Rembrandt | Paintings, Drawings, Etchings | Line, Shape, Space, Value, Color, Movement, Rhythm |

Artwork

Click to view larger image.

More of the Story

Learning the Craft

Q: How did you discover classical Christian education and how did it affect your path as an artist?

A: My first introduction to the classical approach (and the reason I chose a classical education for my children) was at the University of Kansas, which offered an Integrated Humanities program that covered the Great Books of Western Civilization, poetry, and philosophy. The series of classes were taught following the Socratic method used by schools such as Cambridge and Oxford. We memorized numerous poems and read many books that completely changed my view of life and creativity. We read Homer, Virgil, Heroditus, Julius Caesar, the Bible, Cicero, Augustine, Chaucer, Shakespeare and many others. It was during this time that I came in contact with artists from the Golden Age of Illustration, including N.C. Wyeth and Howard Pyle.

My interest in a classical approach to art began in high school with my teacher, Vern Olson, who instilled in me a love of drawing and introduced me to artists such as Rembrandt. At KU, one of my illustration instructors was John Collier, a renowned artist, whose love for the masters and his Christian faith influenced me in a profound way. My landscape painting professor, Robert Sudlow, opened my eyes to the importance of working from observation. He was on the faculty for my study abroad program in Great Britain, where I had the chance to study literature, history, art history and painting. That educational experience, along with seeing the extensive art collections in London, had a significant influence on my life and art.

After graduating from KU, I studied with a classical painter and then attended Atelier Lack in Minneapolis, Minnesota, which was a classical drawing and painting school.

Then, while waiting tables, working third shift in a printing plant and thinking to myself, “I saw this going differently,” my wife found an article about a former Disney animator, Don Bluth, who had moved to Ireland and opened an animation studio. He had previously created animated films such as The Secret of Nimh, An American Tail, and Land Before Time. I didn’t think there was any chance I could get in, but Caroline encouraged me to apply, and I was hired-first for an eight-week trial period, then for a two-year stint that gave me my first experience in animation.

While in Ireland, I worked on films including A Troll in Central Park and Thumbelina, while my wife trained with the British Horse Society.

The experience of working with Sullivan-Bluth Animation in Dublin, as well as the years of training in drawing and painting, opened up an opportunity with Walt Disney Animation-Florida. We moved back to the States where I began a long and exciting career with Disney Animation.

Q: What did you do after Disney?

A: When our Florida studio closed, I became a freelance artist, painting portraits, history pieces and equestrian art. I also began doing concept illustration and scenic art for theme parks and resorts. This was a challenging period because there were few long term projects-most lasted six to seven months. One particular project was Curious George, which I had the opportunity to work on with former Disney colleagues. In addition to working freelance and teaching art online, I was hired as a concept artist for a video game company, which lasted two years before the company shut down.

While this was a trying time, I am thankful for the many freelance projects that came my way and the growing number of opportunities to teach. ✤

~ Stormy Goodwin

[…] The Art of Seeing: Through the eyes of a Disney artist & classical teacher […]