His challenges to reading began early, with two eye muscle surgeries by age four and numerous months of doctor’s appointments, eye patching, and changing glasses prescriptions before he ever entered the doors of his classical school. Desiring to give our son a firm foundation in language, I met him daily at his school during his lower school years, slowly building visual and perceptual skill where there were noticeable weaknesses. At home, we read aloud, played audiobooks often, and looked for other ways to expose our child to language and story. My husband and I read and researched, met with teachers, and prayed for wisdom. We sought the counsel of experts, exercised creativity, and learned patience in ways we had never known. And somehow—over the course of years—our son’s reading was transformed.

For struggling readers in the classical school, approaching the reading life is fraught with concern. Parents—and sometimes teachers—silently ask: Will this child ever learn how to read? Is she benefitting from these stories? Will he ever be able to access the classics?

Knowing that the early grades emphasize learning to read—and later grades rely heavily on reading to learn—such a struggle often induces discouragement, panic, and fear. Yet the truth remains: reading assessments are not indicative of a student’s value—and, despite the parameters of classroom learning, no child is on a time clock. If our philosophy of education is truly focused on the cultivation of wisdom and virtue in the lives of children who bear the mark of the divine, we cannot afford to confuse age-graded skill proficiency with the ability to pursue the reading life. Some children may require extra instruction, modified curricula, increased repetition, and/or a slower pace, but such a journey is worth the effort; the classics are for struggling readers, too.

This isn’t a claim I come to on purely philosophical grounds; I have lived it alongside my own child.

Classical education regularly reminds us of the immense fruit to be gained from the reading life. Such a life offers access to information and ideas, an open door to freedom and opportunity, and a powerful means for coming to know both others and ourselves. We read to experience community, to better understand humanity, and to enter into the Great Conversation that has shaped the history of human thought and is shaping us still. Some texts call us in with ease, and others are more difficult to access; a classical education makes use of both, believing that the effort required to read good literature is worth its yield.

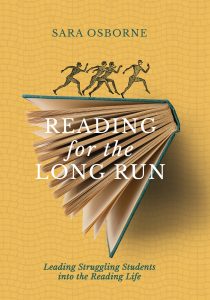

October witnessed the release of my new book, Reading for the Long Run: Leading Struggling Students into the Reading Life. Among chapters about motivation, planning, problem-solving, and assessment for struggling readers are pages that bear witness to the fruit of our own journey. Over the course of many years (read: a long time), much concerted effort (read: doing it when you don’t want to), and countless prayers (read: God, help us both), our child has made gains I once struggled to imagine. He’s not only a better reader; he’s a changed person. His character-honing journey into the reading life bears witness to the upside-down kingdom of God: weakness is the way.

This week, my husband and son sat down to take turns reading The Fellowship of the Ring. Line by line, chapter by chapter, our child is reading what his teachers have taught and scholars have studied and his parents have marveled at and his older sisters have grown to love. He’s reading a text that will call him into adventure and remind him of the often-deceptive lure of power. He’s witnessing the choices of characters that will help him better examine himself. He’s stepping into an inheritance of words and sentences and paragraphs that have transformative power. Shaped by the diligence, discipline, patience, and humility he has learned over many difficult years of learning to read, he is stepping into his own reading life.

We are not strangers to the limitations of human weakness. We daily witness our children’s and our own. For now, our son’s visual processing challenges will likely mean that his eyes tire more easily, he needs larger-print books, and he requires more time to read and absorb a passage of text. Other struggling readers may encounter different obstacles that require anywhere from a school year to a lifetime to address. But the telos of reading—indeed, the telos of education—is the same for the struggling reader as it is for all our students; the fundamental purpose of education is to grow our children in wisdom and virtue. If good books encourage such growth, then we all need them; despite the difficulty of the journey, struggling readers need the classics, too.

~Sara Osborne serves as Assistant Professor of English and Director of Classical Education at College of the Ozarks in Point Lookout, MO, and is the mother of four classically educated children.

~Sara Osborne serves as Assistant Professor of English and Director of Classical Education at College of the Ozarks in Point Lookout, MO, and is the mother of four classically educated children.

Read Sara’s newest book, Reading for the Long Run. Part memoir, part interview, and part research-based support, this book offers guidance for the teacher of a struggling reader. You can find it here.