Virtue and the Really Real

By David Goodwin

When a child at an ACCS school studies a great book, politely says, “Yes, Mrs. Cooper,” opens a door for a stranger, or correctly divides a fraction, he is participating in a higher reality. Over time, with practice, his affections are drawn toward the good, the true, and God’s ideal of beauty. This is how classical schools cultivate virtues of all types– moral, intellectual, and natural. We train children to aspire to something greater. In contrast, progressive (public) schools focus on skills for navigating the “real world.” If your children attend a classical Christian school, you might notice the difference and wonder: Is the difference just the uniforms, Latin, and good manners? Do these things help them get a job or raise a family?

Even America’s progressive teachers’ colleges label classical education as “idealistic,” contrasting it with their “realistic” mainstream approach. Progressive schools may teach fractions or read socially conscious books, but their education falters because it cannot look upward. To look up is to gaze toward heaven– something we’re told must not be done.

Modern Christians often see heaven simply as a destination after death—the place of angels and God. But in a classical context, heaven is where ideals are real. On earth, reality is a corrupted version of the good. Augustine taught us this: “Evil has no nature of its own; it is merely the absence of good, which we call ‘evil.’” If this is so, the most realistic thing we can do is seek to make the ideal real.

What others dismiss as “idealistic,” Christians should see as the “really real.” Otherwise, we risk chasing the fallenness of the world. Progressive educators often do this—they distort sexuality, label reason as racist, and contribute to a culture where language grows crasser, clothing becomes casual and immodest, music and art turn ugly, and manners give way to outrage and indignation.

Classical and progressive schools pursue different goals, shaping the graduates they produce. When education focuses solely on what “works” in the real world, our gaze drops downward. American education began sliding toward this low point around the turn of the 20th century, when it turned away from Christian truth as the basis for what is real.

When education mirrors the world’s corrupted reality, children reflect that corruption rather than heaven’s truth. No culture, civilization, or family has ever ascended above their current state by pursuing a corruption. Instead of “repairing the ruins of our first parents,” as John Milton put it, we conform to the ruins around us. Classical Christian schools engage the present reality as it is, but with an aim to mend it—aligning it with God’s original creation. We strive for the “really real”—the reality God made and called “good” in Genesis.

In raising virtuous children, we want them to conform to this higher reality. We encourage them to seek greater goods while progressives urge them to “be true to themselves.” All education shapes virtue—either true virtue or false virtue (vice). Without Christ as a compass, secular schools, no matter what they teach, cultivate false virtues, modeling only the corruption they see. This fundamental flaw in secular education produces students who confuse good with evil, bitter with sweet, and darkness with light. Isaiah 5 warns that this path leads to a curse, not to God.

Classical schools teach virtue not as mere behavior, but as submission to the ultimate reality of Christ. In this way, “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven” is more than a prayer, it’s what we train our children to love. Classical Christian education does more than prepare children to “get by” in the real world—it equips them to improve it.

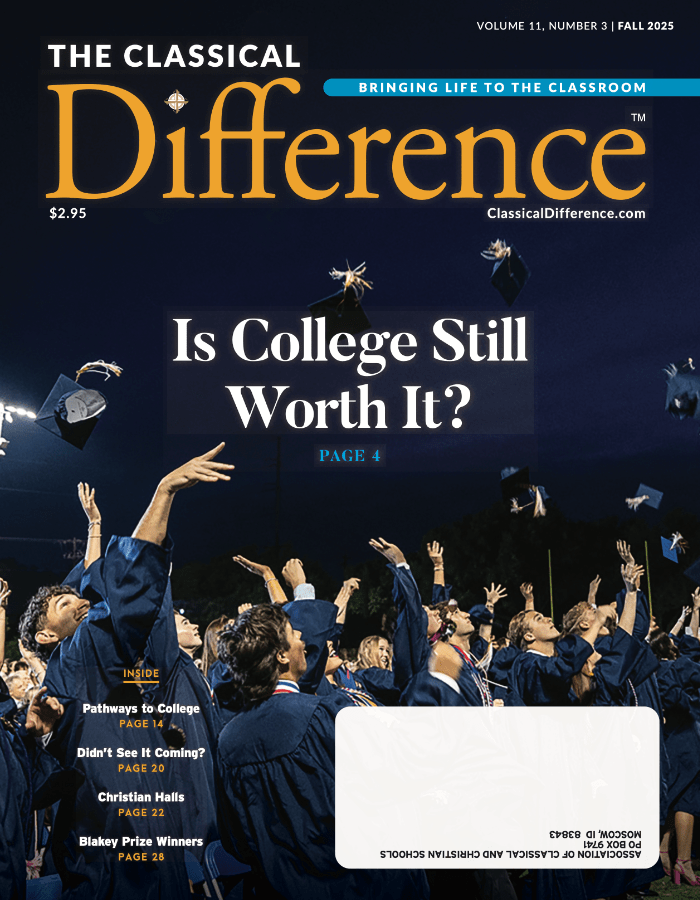

Photo courtesy of Geneva Classical Academy (Lakeland, FL)

DAVID GOODWIN is a pioneer in the classical Christian movement, and co-authored the #1 New York Times Bestseller, Battle for the American Mind, with Pete Hegseth. He helped found The Ambrose School in Meridian, ID, and was headmaster there for 13 years, growing it from a struggling small school to over 500 students and building its current facility. He has been the president of the Association of Classical Christian Schools since 2015.