By David Goodwin

When I ask “who was the hero in that movie?” my kids groan. They know more questions will follow. And, I know their next words: “Dad, this isn’t school.” Thankfully, our classical Christian school asks questions like this, too. Maybe, if I can convince a few more parents to ask questions like this on the way home from the movies, I’ll head-off the next predictable line from my kids: “No one else’s dad asks these questions!” So, with that in mind, here goes…

The recent movie Ford v Ferrari reveals how we see our heroes. The bones of the story are enticing: In the 1950s, Ford made “functional transportation” and needed a better image. Ford sought to buy Ferrari because of their legendary dominance at Le Mans—the world’s most prestigious auto race. Enzo Ferrari rebuffed Ford, and an epic rivalry was born.

Ford and Ferrari would proceed to engage in now legendary auto industry battle at the Le Mans race in 1964, 1965, and 1966. Ford, the newcomer, out-spent Ferrari on an unprecedented scale. At one point, Ford famously bought the entire first-class cabin of an airliner to express ship new windshields to Le Mans for the race. Ford recruited the unconventional but talented team of Carroll Shelby (designer) and Ken Miles (driver). After three tries, Ford finally won.

Ford and Ferrari would proceed to engage in now legendary auto industry battle at the Le Mans race in 1964, 1965, and 1966. Ford, the newcomer, out-spent Ferrari on an unprecedented scale. At one point, Ford famously bought the entire first-class cabin of an airliner to express ship new windshields to Le Mans for the race. Ford recruited the unconventional but talented team of Carroll Shelby (designer) and Ken Miles (driver). After three tries, Ford finally won.

As the story goes, American ingenuity and economic might prevailed against a giant of auto-racing: Ferrari. To this day, Ford is the only American manufacturer to win Le Mans. As we read, watch, or hear stories like this, one of the most important questions to ask our children is, “Who is the hero in this story?” And, more importantly, “Why?” Is it Ford because Ford won? Is it Shelby because he built the team? These questions lead us beyond cars and racing to see the influences of our culture on subtle messages we ingest every day without thinking about it. Since this movie parallels another ancient story, it makes a good example for explaining how classical Christian education helps our graduates see what others do not.

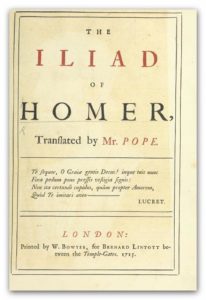

A teacher I know once asked his students, “Who is the hero? Achilles or Hector?” referring to the seminal Greek epic, Homer’s Illiad. Achilles is the Greek war hero who brings about victory over the Trojans. Hector is the self-sacrificial leader of the legendary city of Troy who joins in single combat with the unbeatable Achilles in an effort to save his city. It doesn’t end well for Hector. Yet, nearly all the students chose Hector as their hero. The Greeks who wrote the story saw Achilles as the hero—two juxtaposed views. How can two groups of people see opposing heroes from the same story? Who tells the story is one factor—but the Greeks wrote the story! Even more significant is the paideia, or enculturation, of those hearing the story.

In the movie, Ferrari’s story is scantily told. Like Hector, Enzo Ferrari had a small but loyal team of brilliant engineers, some of whom were offered and refused much more money to come over to the Ford side. Ferrari’s race team had a fraction of Ford’s budget. They focused on refinement. Where Ford put power, Ferrari tweaked air-flow and fuel efficiency. Where Ford bought the best drivers, Enzo cultivated his team. Ferrari’s story is one of loyalty, tenacity, faithfulness, and fortitude. Against this type of virtuous resistance, victory took three years for Ford and ten for Achilles.

more money to come over to the Ford side. Ferrari’s race team had a fraction of Ford’s budget. They focused on refinement. Where Ford put power, Ferrari tweaked air-flow and fuel efficiency. Where Ford bought the best drivers, Enzo cultivated his team. Ferrari’s story is one of loyalty, tenacity, faithfulness, and fortitude. Against this type of virtuous resistance, victory took three years for Ford and ten for Achilles.

The epic connections go further.

There is some irony in the fact that Enzo Ferrari, of course, was Italian. Virgil, another Italian, rewrote the myth of Troy a thousand years after Homer, but with a new hero—Aeneas. Aeneas was not known for his victory in battle, but as a fleeing, defeated Trojan general who sought to found a new home for his people. Like Hector, he does so with fortitude, loyalty, tenacity, and self-sacrifice. This myth, in effect, built Rome—not in a day, but as myths will do, over centuries. If Ferrari’s virtues were influenced by Aeneus’s epic, it seems Ford’s virtues reflected those of Achilles from the Greeks.

In one scene, the Ford team jokes about a pair of pilfered stop watches from the Ferrari team, reinforcing the cowboy image of the Americans. In another, a manufactured-for-Hollywood brawl breaks out between Shelby and Miles (no such fight happened in the real story). Team Shelby uses cunning to replace entire brake assemblies instead of brake pads, exploiting a technicality in the rules. These small plot spins reflect the film’s appeal to American collective virtues. We like cowboys. Getting there “by any means necessary” has a naughty but practical ring to it. We Americans have fancied ourselves this way since we embraced the term “Yankees” at our founding (as in “Yankee ingenuity”). The movie’s mythical status reinforces these virtues as it plays to our affections. At one point in the movie, Henry Ford garishly departs the track during the race in a helicopter. Enzo comments sarcastically: “That’s classy. Take a helicopter to a car race.” In another, we see Enzo tip his hat to Miles after the win. Glimpses of Hector as Enzo are there to see. Many of us probably saw the tip of the hat as an ode to Ken Miles rather than an exhibition of honor by Enzo.

In one scene, the Ford team jokes about a pair of pilfered stop watches from the Ferrari team, reinforcing the cowboy image of the Americans. In another, a manufactured-for-Hollywood brawl breaks out between Shelby and Miles (no such fight happened in the real story). Team Shelby uses cunning to replace entire brake assemblies instead of brake pads, exploiting a technicality in the rules. These small plot spins reflect the film’s appeal to American collective virtues. We like cowboys. Getting there “by any means necessary” has a naughty but practical ring to it. We Americans have fancied ourselves this way since we embraced the term “Yankees” at our founding (as in “Yankee ingenuity”). The movie’s mythical status reinforces these virtues as it plays to our affections. At one point in the movie, Henry Ford garishly departs the track during the race in a helicopter. Enzo comments sarcastically: “That’s classy. Take a helicopter to a car race.” In another, we see Enzo tip his hat to Miles after the win. Glimpses of Hector as Enzo are there to see. Many of us probably saw the tip of the hat as an ode to Ken Miles rather than an exhibition of honor by Enzo.

Virtues are those affections we hold deep inside us. Cultural virtues are passed to us without our realizing it. Classical Christianity challenges cultural virtues to refine them, and seeks to improve the cultures in which we live. This has been the common grace gift of Christianity for two millennia. Do our culturally transmitted virtues call us to love the right things? Do they make us love the right things in the right order? Many of the “virtues” in our media and movies are false virtues, and our children are absorbing them. What can we do to prevent this?

We can teach our children to see what is happening to them. Classical Christian education exposes students to these great myths like the Iliad and the Aeneid and holds up their heroes to the light of Scripture. Unlike the authors Homer or Virgil, we have the gift of Truth in the person of Jesus Christ. We can teach students the art of seeing through blind conformance with the false virtues in our culture, as well as the art of identifying and refining those that are good. This skill is best developed using historical myths and historical cultures as our subject. Then, we can show our kids how the same tools of virtue evaluation can be used every time we see a movie, read a book, or look at Instagram. This skill has never been so critical.

Virtues, aligned with Christian truth, goodness, and beauty are powerful. Virtues based in error—or simply wrongly ordered—are also powerful. And, they are  dangerous. If our students can come to see every story and every character as a source of heroes who have virtues, then they can rightly divide truth. This is our call as Christians. Put your children’s classical education to work this weekend when you watch that movie. Ask them who the heroes are and why. They may roll their eyes (if they’re teens), so you need to push them to think more deeply than the obvious. Maybe Enzo Ferrari deserves another look. After all, the image of a Ford today is, well, a Ford. A Ferrari is still a Ferrari. In the long-game of reputation, who won?

dangerous. If our students can come to see every story and every character as a source of heroes who have virtues, then they can rightly divide truth. This is our call as Christians. Put your children’s classical education to work this weekend when you watch that movie. Ask them who the heroes are and why. They may roll their eyes (if they’re teens), so you need to push them to think more deeply than the obvious. Maybe Enzo Ferrari deserves another look. After all, the image of a Ford today is, well, a Ford. A Ferrari is still a Ferrari. In the long-game of reputation, who won?

HEROES ASIDE, Ford v Ferrari is a worthy movie for older families. There’s some language, but otherwise the father-son relationship between Ken Miles and his son

is worth the price of admission. The director, James Mangold, does an impressive job of moving the plot along while developing the characters. Far from a car-guy flick, the film tells a story as well as any movie you’ll watch this year.