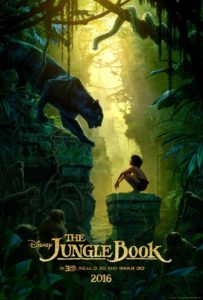

Top Photo: “The Jungle Book,” 2016 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

Winter 2016

The rarest of cultural alignments occurred

this past year

The same story, retold for and by three different generations, is the worldview equivalent of layers in an archeological dig. In three versions of The Jungle Book, we can see three distinct views of “the good life” that reflect the changing cultural scene in America.

Taken from the long tradition of fables, The Jungle Book shows us “the good life” through personified animals, a primitive human culture, and a petri dish of worldviews. Just as Aesop’s Fables, 1001 Arabian Nights, and Grimm’s Fairy Tales shaped virtues in three distinct civilizations, The Jungle Book reveals our civilization, and imprints in different ways on our kids.

Classical education makes us aware of an underappreciated power: the vision of “the good life.” Every culture is shaped by the vision of what life we should pursue—our founding fathers called this the pursuit of happiness. What makes us happy is largely a function of vision, cultivated at a young age (go to school and college, get married, have 2.5 children, etc.). This vision carves our children’s track through life. Parents should teach their children two simple questions to ask every time they watch a movie or engage in a story: “What is the vision of ‘the good life’ in this work?” and, “Is this really good?”

Rudyard Kipling released The Jungle Book as a series in the 1890s. The second major retelling was in the 1967 Disney animation release. With Disney’s live-action release of the 2016 Jungle Book, we see the third major retelling of this story. (We’ll call them “Kipling’s,” “JB ’67,” and “JB ’16.”)

All three versions are well done and excellent in their own right. Kipling’s rich storytelling will leave your child with a sense of awe from deep in the Asian jungles that will be burned into their imagination for life, especially if read to them at bedtime! JB ’67’s soundtrack has some of the best jazz music written for children. And the stunning visual imagery and compelling depiction of Mowgli by Neel Sethi in JB ’16 is well worth a rental, if you didn’t see it in the theater.

None of these depictions are avant-garde. They reflect the culture that “is” more than they try to influence it. They are just playful stories. This is what makes them such good artifacts to help understand “us.” Kipling’s work is very different from the 1967 or 2016 retellings. The original Mowgli is a boy of two natures. His prideful, playful, and sometimes rebellious nature requires his animal custodians to discipline him. But, he’s also regal. The animals cannot look him in the eye. His authority over them is based simply in the fact that he’s a man-cub. Clearly, we see Kipling’s Christian understanding of Mowgli—a divine image bearer, yet fallen. And, we see an understanding of hierarchy, rather than equality. We see this most clearly in the banderlog—a lawless civilization of monkeys. Mowgli is attracted to the banderlog, not by fire as with Disney’s renditions, but because they want him to be their king. Of course, they’re lousy subjects, so this doesn’t work out.

When Walt Disney himself commissioned a team to put Kipling’s tale on the silver screen, he wanted something happier and more playful than Kipling’s original. We see a Mowgli who is fun loving, curious, and likable. JB ’67 was Walt Disney’s last anachronistic work to depict his view of “the good life” as redefined for Americans by Disney himself from 1945–1970—fun music, indulgent friends, a Mowgli-gets-thegirl scene, and a villain who gets burned (but not killed) in the end. Walt’s formula, from Snow White to The Jungle Book, did more to imprint values of “if it feels good, do it” and “free love” on the idealistic hippies than any college professor could.

In the 2016 version, the boy is not regal, he’s more “authentic.” In JB ‘16, Mowgli is a reflection of our dependence on technology—he builds simple machines to win races, get honey, and thwart Sheer Khan. This gains the friendship of the animals. And, in the end, technology (tools) wins the day. Mowgli’s ultimate victory comes through cooperating with nature’s king—the elephant. A reverence, almost worship, of nature and the belief that overcoming adversity just requires a bit of technology has been borrowed from a generation attached to i-devices while they victoriously climb El Capitan.

By “excavating” three generations, we can see what cannot be seen year-to-year. Kipling’s Christian, yet romanticized, view of “the good life” leaves children with a sense of wonder and a healthy fear of the evil in our world, and a virtuous response to that evil. Walt’s innocent and indulgent view helped to create a generation that needed every problem to be fixed, the outcome to be just, and above all, the pursuit to be fun. Where prior generations saw family, children, and the resources to support them as “the good life,” Disney reflected and helped reshape “the good life” as no obligations, no rules, just right. And, in the most recent telling, we see a good life marked by harmony and dependence on nature, and the boundless potential of the individual.

We can see the Christian worldview is not something that is spelled out in sermons or even read directly by citing verses of Scripture. Rather, it’s a subtle view of what constitutes a life well lived, informed by the whole of Scripture. What do your children believe about “the good life?”

Clarity in Contrast

TWO VIEWS OF “THE GOOD LIFE”

In 1964, Walt Disney was disappointed with Bill Peet after he created an initial, faithful interpretation of Rudyard Kipling’s classic The Jungle Book. Disney wanted something less lush and moody, and less serious. He hired a new director, Larry Clemmons, to direct The Jungle Book with one condition: “The first thing I want you to do,” instructed Disney, “is not to read it. I want you to have fun with it.” The product, released in 1967, bears the result of Disney’s request. In Disney’s released version, the monkeys steal an innocent Mowgli, prompting his “friends” Bagheera and Baloo to save him. At the end of the battle with the monkeys, Bagheera and Baloo discuss what happened.

1967 DISNEY RELEASE

BAGHEERA: “Mowgli seems to have man’s ability to get into trouble.”

BALOO: “Keep it down, you’re going to wake up ‘little buddy.’ He’s had a big day. It was a real sockeroo. It ain’t easy to learn to be like me … you know.”

BAGHEERA: “Associating with those undesirable, skatter-brained apes? I hope Mowgli learns something

from that experience.”

The scene ends as Baloo tucks him in. Throughout the rest of the show, Mowgli’s crisis is in finding a friend he can trust. It turns out to be a girl.

In Rudyard Kipling’s 1894 original, the story is a bit more sordid, with a deep moral. After Mowgli has been found befriending the monkeys, he’s scolded by his guardians, Baloo and Bagheera. Mowgli’s pride and rebellion bring him to temporarily disrespect his teacher, Baloo.

THE ORIGINAL

MOWGLI: “They were kind … They stand on their feet as I do. They do not hit me with their hard paws. They play all day … I will play with them again!”

BALOO: “Listen, Man-cub,” his voice rumbled like thunder on a hot night, “I have taught thee all the Law of the Jungle for all the people of the jungle, except the Monkey-folk who live in the trees. They have no law. They are outcast … They have no remembrance. They boast and chatter and pretend that they are a great people about to do great affairs in the jungle, but the falling of a nut turns their minds to laughter and all is forgotten …”

BAGHEERA: “His nose is sore on thy account. As are my ears and sides and paws, and Baloo’s neck and shoulders … all this from your playing with the [monkey people].”

MOWGLI: “True, it is true. I am an evil man-cub and my stomach is sad in me.”

BALOO: “Sorrow never stays punishment.”

These examples are but the tip of the iceberg in the recurring moral simplification and dumbing down of great stories, which yield shallow, simplified morals in our kids. We encourage you to read the original Jungle Book to your children this holiday season.

Virtues in Motion

We can glimpse the shifting vision of “the good life” over the past 100+ years by looking at just a handful of examples from The Jungle Book retellings. “The good life” for both Kipling and JB ’16 involves jungle law, but the source is quite different. Kipling’s original concept of the law is more like C.S. Lewis’s “deep magic” inscribed on the stone table—it’s coded into creation by the creator and known by everyone (Romans 1).

For example, Mowgli’s life is bought by Bagheera for the price of a kill—a bull—based in the law of the jungle. In JB ’16, we see this law become a social contract. The animals all benefit mutually as they agree to follow the law—no killing at times of low water because then everyone can get a drink. We can see the contrast between God’s law, built into nature, and today’s concept of law as a social contract, flexible and practical. How does this influence your child’s understanding of right and wrong?

In JB ’67, we see a different view of children. In Kipling’s work, it is considered bad manners to compliment children in front of them. Yet in Disney’s view, we see the parent figure, Baloo, calling Mowgli “little buddy.” Kipling’s Baloo was a parent/disciplinarian (Hebrews 12:7). Disney played a keen role in moving the vision of parenting from one who loves and disciplines children to one who loves, befriends, and indulges children.

Throughout Kipling’s story, the vision of “the good life” is family. This can clearly be seen in Mowgli’s motivation to return to his village. In Kipling’s original, Mowgli is drawn by his mother and relatives there. In JB ’67, Mowgli returns for an attractive girl. We can see a vision of “the good life” emerge—the pursuit of family versus a romantic/sexual motivation.

The consequences of ideas, and the consequences of stories, are more powerful than we think. Of course, The Jungle Book stories reflect these attitude shifts; they are not solely responsible for creating them. It takes hundreds of stories to do that.