The sweetest thing in all my life has been the longing … to find the place where all the beauty came from.

—C.S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces

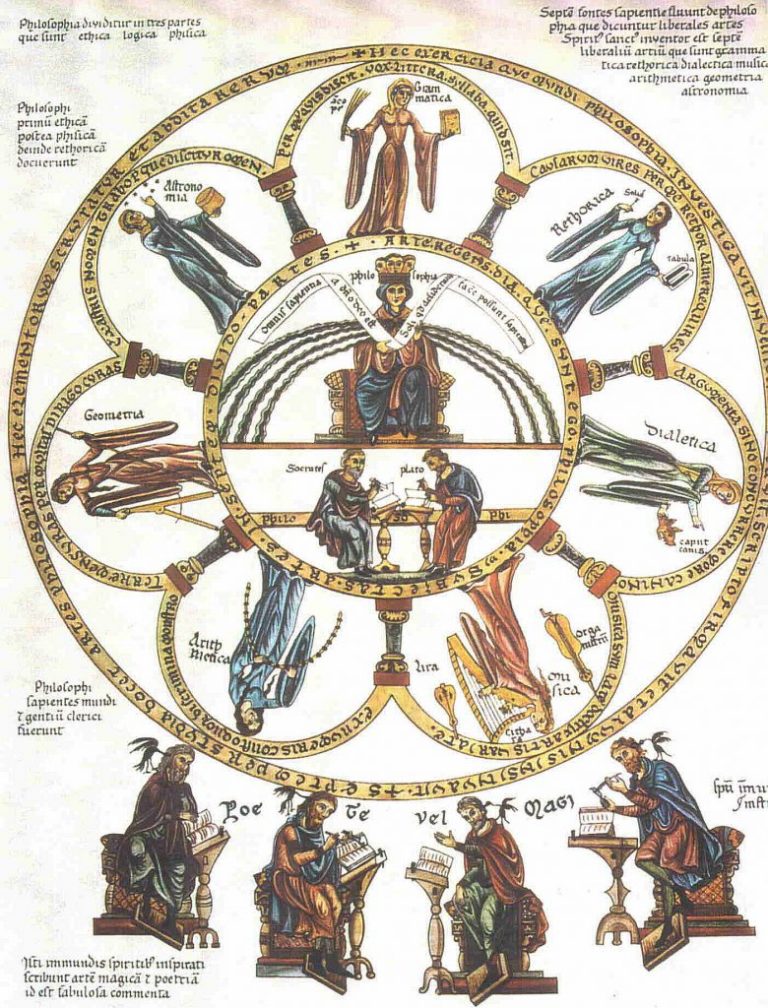

Liberal Arts in the Hortus Deliciarum

In the late 1100s Herrad of Landsberg, a nun at the Hohenburg Abbey, put together “The Hortus deliciarum” (Latin for “Garden of Delights”), a collection of manuscripts on various topics — an encyclopedia of sorts — for the novices at her abbey. One of these manuscripts pictures the seven liberal arts, also known as the trivium and quadrivium. Grammar stands at the top with Dialectic and Rhetoric following clockwise.

Below Philosophy, seated at desks, are Socrates and Plato, identifed as those scholars of the Gentiles and sages of the world who first taught ethics, natural philosophy, and rhetoric.

North Tower, Laon Cathedral, France (pictured at the top of this article)

IN THE 13TH CENTURY, a crew of planners and artists in Laon, France, spent hundreds of hours building a stained glass window. The north tower window of Laon Cathedral became a testament to the trivium and quadrivium—the outside circle of images—and their queen, theology, in the center.* This “seven liberal arts” theme is found throughout Europe’s medieval cathedrals because of its centrality to the faithful life.

Most people’s desire for greatness is for human, earthly gain. When we see the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages, we see an effort to reach beyond any one pocketbook or any one life. Each of us longs for higher, lasting things. The Western Christian tradition is like a searchlight helping us find our way because it shines beyond what our limited senses can perceive. As the writer of Ecclesiastes states, “God set eternity in our hearts.”

While we in modern America design our buildings and our homes, and decorate those areas, with very little more in mind than functionality and trending fashion, the centrality of the search for Truth is reflected throughout medieval architecture.

In the Notre-Dame de Laon cathedral, known for its Gothic architecture, the Northern Rosace (pictured at the top of this article) represents the seven liberal arts and medicine studied at the Episcopal School of Laon. Philosophy is in the center. Clockwise from twelve o’clock the outside windows represent rhetoric, grammar, dialectic, astronomy, medicine (not one of the seven), geometry, and music.

Learn more: https://www.abelard.org/france/cathedrals5-laon.php#rose

Bodleian Library, Oxford

Each door leading from the common area outside the Bodleian Library, into what used to be lecture rooms for each area of study, has the name of the area written above it in Latin. Three rooms are dedicated to the quadrivium. One room combines arithmetic and geometry, and music and astronomy each have their own. The trivium has four rooms, with grammar split into two sections: one for history, one for Hebrew and Greek. Below are pictures of the Schola Logicae (school of logic), the Schola Lingarum: Hebraicae et Graecae (school of languages: Hebrew and Greek), and Schola Astronomiae et Rhetoricae (school of astronomy and rhetoric which leads to two separate rooms).

Chartres Cathedral

The Western entrance to the Chartres Cathedral in France was sculpted in around 1150. The door on the right depicts the trivium and quadrivium in the sculptures in the arch. In the top row, each art is personified. Directly below the personification is a sculpture of a historical person: Aristotle under Logic, Cicero under Rhetoric, Euclid under Geometry, Boethius under Arithmetic, and so on.