by Amy Burgess | Fall 2016

Real Judges, Real Courtrooms, Real Life

Start a Team | 2016 Nationals | In the News | Designed for CCE | National Mock Trial | Underdogs Head to State

“I’LL TAKE THAT UNDER ADVISEMENT,” a magistrate judge from the State of Colorado responded after a quick objection by a tall, sharply dressed student-attorney from Duchesne Girls School, the reigning national champion. Another Duchesne witness continued, angry and desperate. “I know that rancher killed my sheep!”

Spectators wondered if she would break out of her accent as the cross examining attorney pressed. “Yes or no, Ms. Zaballa? Did you see the defendant anywhere near your sheep?” The Ambrose School’s attorney held her gaze until a quiet ‘no’ reluctantly came. He turned to the jury. “No further questions.” At the U.S. Mock Trial Nationals, the best team from each state competes for the national title.

In a courtroom in Texas, the witness on the stand sobbed loudly, his head in his hands, his shoulders shaking. His pet, Pixel Poo Poo, had been killed when an angry neighbor shot a drone out of the sky and it crashed onto the dog. The attorney directing the questions at the witness gently asked, “Do you need a minute, Mr. Barkley?”

The audience snickered. The judge stifled a laugh. This witness was good. Really good.

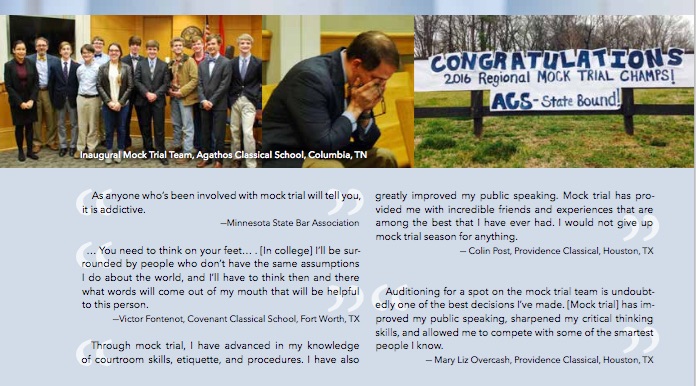

In Tennessee, home-schooled teenagers wearing suits sat nervously behind the counsel table at the front of the courtroom awaiting the verdict. When the judge announced their victory, they jumped from their seats and hugged each other in relief and elation—it was a well argued case, and the victory was deserved.

Logos School, Moscow, ID

In the sometimes bizarre world of high school mock trial competitions, 9th–12th grade students take on the roles of witnesses and attorneys in fictitious court cases. They spend countless hours over the course of several months preparing their roles. Witnesses memorize witness statements (or affidavits)— they must “become” their character if they are to withstand the grueling cross examination from an opposing team’s attorneys. Teen attorneys write compelling, persuasive opening and closing statements, prepare their own witnesses for direct examination, and craft strategic questions for the cross examination of their opponent’s witnesses.

At regional competitions each winter, in more than 40 states and U.S. territories, teenagers wearing power suits and brandishing exhibits take sides and argue their cases in front of a judge and jury of volunteer real attorneys. The jury rates the individual students on their performances, and ultimately awards each round to one team. The winners of the local competitions go on to compete in their state’s competition, and the state winners battle it out at the national com- petition each May.

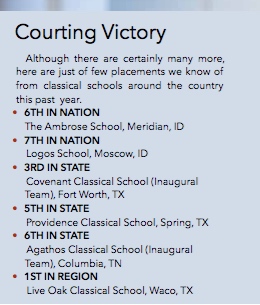

At these competitions, you can see high school students doing things you didn’t know humans could do, says Chris Schlect, head of the mock trial program at Logos School in Moscow, Idaho. Schlect has coached more teams to nationals than any other coach. He became the coach when he was a teacher at Logos, but even when he left Logos to become a Fellow of History at New Saint Andrews College, he could not leave coaching mock trial behind. Logos has qualified for the national competition 14 times, ranking as high as 5th in the nation. This year they placed 7th, just behind their sister classical Christian school, The Ambrose School in Meridian, ID, who placed 6th.

Mock trial is an extra-curricular activity that classical students are particularly well-suited to, says Schlect, because they have been trained to think logically, to make eloquent, persuasive arguments, and to work hard. It is a practice in excellence.

Mock trial is an extra-curricular activity that classical students are particularly well-suited to, says Schlect, because they have been trained to think logically, to make eloquent, persuasive arguments, and to work hard. It is a practice in excellence.

“The ability to parse and to break down something as complicated as a mock trial problem, and to identify it’s most meaningful, significant, and relevant aspects, is an incredible life skill,” Schlect says. “And I think classical schools inculcate that throughout their entire program.”

Maggie Church was part of the 2005–2008 mock trial teams at Logos, and in 2008 she received an award at the national tournament for the best all-around mock trial participant. Church teaches at Logos now and helps coach their mock trial teams. She says mock trial encompasses all of the trivium, fitting perfectly in the rhetoric stage of a classical education.

The Ambrose School A Team, 6th Place, 2016 National Mock Trial Competition

“My education taught me how to learn, and that really is the most helpful when attacking a 90-page case in six weeks at the national level,” says Church. “You memorize the building blocks of law, rules of evidence, and the case materials. You analyze arguments and build them yourself. Then you have to present it all winsomely in a way that makes sense to a jury member.”

Being part of a mock trial team requires hard work and long hours. “It means an entire season of sleep deprivation, of sweat, of getting ruthlessly criticized by the coaches and knowing that that’s just how it is,” says Chris Schlect. But the intensity of the criticism is balanced by equal intensity of laughter and camaraderie, for he continues, “You can’t take yourself too seriously in mock trial.”

For Maggie Church, mock trial has created some of her strongest, most lasting friendships. “When you are working side by side for six months, through edits, re- visions, early mornings, late nights, stress, laughter, and all the craziness, you really have a deep bond,” Church says. “My mock trial teammates saw me at my worst and my best. You have to be there for each other at counsel table—you have to trust them and rely on them for everything.”

Mock trial. It’s all about the things we want for our kids—intelligence, grit, wisdom, leadership, community—and at a level almost impossible to reach in any other school activity.

![]()

by Amy Burgess